So you study propaganda? What Soviet magazines have to do with your food photos…

May 8, 2017

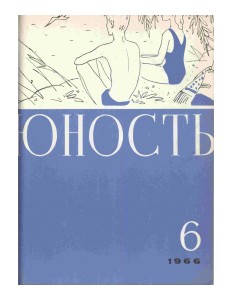

The last couple of months I’ve been talking a lot about my research in non-academic (and non-Russian) social contexts more often than I used to. Needless to say, I believe that this is our mandate as humanities scholars – now more than ever. But the truth is that I’m also feeling increasingly confident about my own work. When I say I study literary journals in the Soviet 1960s, the ways in which they organize how authors write and how readers read, people usually respond: “So you study propaganda…?” And the first couple of times I was baffled.

Propaganda isn’t a term I think about particularly much in my own work. In fact, it’s quite the opposite I’m after in my dissertation, which tries to show how late Soviet culture developed a surprisingly rich set of independent cultural forms – journals with unique visual identities, distinct groups of authors with competing sets of aesthetic and ideological ideals, committed readers with strong potential for identification.But I also understand where my interlocutors at dinner parties come from. Popular Cold War representations of conformity in the socialist block govern American thinking about Soviet everyday life, where people seem to have lived in complete control and constant fear of a state that was consistently brainwashing them. Of course, this is pretty far from Soviet reality (at least during the later years), but how do I say this without sounding like a revisionist know-it-all, who, in the ears of my interlocutor, must dismiss the GULag or the dissident movement. That’s not the point of my research and there would be no social gain in me doing this research.

Yes, in the Soviet Union, access to the means of cultural production as well as to audiences was restricted. Quite literally – you couldn’t go buy a printing press (or a copying machine). And even if you managed to print something, you couldn’t just disseminate it openly. There were institutions who controlled these access points and they had a whole set of rules that defined what could be published. Finally, there were people in control of these conditions that had concrete agendas for what they wanted to achieve with their work – inform, educate, convince, manipulate audiences in one way or another.

At different points in Soviet history, these restrictions were more or less severe. And there were written and unwritten rules for what could be done within this framework. In the 1960s and 1970s, the rules were fairly predictable, and people developed knowledge about how to play according to these rules – with results that were entertaining and artistically pleasant. That’s in part what my dissertation is about.

For me, this is a more truthful representation of how media in the Soviet Union worked. And it shouldn’t feel completely alien. In our contemporary world, the means to media production are extremely restricted. You can’t just start a magazine and it certainly takes even more (read: marketing $$$) to reach a broad audience. Even the themes you can talk about are pretty limited – not only by the law, but by anticipated audience and advertiser taste.

But we also have a strong instinct that lets us develop our own tactics to play within a system of restrictions. You can see this especially in social and online media. Let’s say you want to be an Instagram star. Not only does Instagram have rules of what you can and cannot post, it also controls what is successful. I’ve been having this experiment with my sister for a while. We made two accounts for food photos and observed what fared best with Instagram algorithm and the inclination of Instagram’s audience. And guess what: people will still love an ugly food photo – as long as it’s photographed from above and hashtags avocados. A soup from a can, as my sister proved, is much more loved than a cake you worked on for half a day and photographed from the wrong angle (i.e. not from above) with the wrong hashtags (truthfully, no avocado). You cannot possibly convince me that it had to do with the subject of the photo – unless you find me a person that likes canned soup better than a homemade cake.

Maybe this is a terrifying dictatorship of algorithms mixed with people’s pre-determined taste, but then you have people that succeed within this framework and do good things. We shouldn’t fear Soviet media or Instagram by calling them evil propaganda machines. Over and over again, we are simply surrounded by complex, prescriptive and prohibitive systems that control how cultural forms – be it a journal cover, a poem or a food photo – are produced and read. And yes, calling them empowering or democratic is an illusion. Nevertheless, within these systems, we learn to play, while they never stop playing us back. That’s what my dissertation is about.